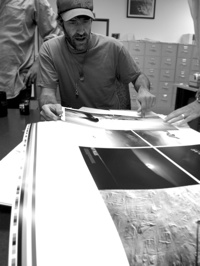

“There,” Chris Brunkhart says, jabbing his index finger into a proof sheet from his new book and sliding it across the table. “Blue sky.”

Someone had rather impolitely asked Chris if his new collection of 1990s era snowboard photography How Many Dreams in the Dark included even one blue sky image. Chris seems relieved to be able to point one out so quickly. And technically, he is right. There is a bit of blue sky. But it is a Brunkhart version of a blue sky. The sun nearly set. Sky darkened to almost black as snowboarder Matt Donahue blasts one more method through the lengthening rays of an already winter-shortened day at Washington’s Steven’s Pass.

In snowboard photography, where bright colors, blue skies, and white snow sell covers, ads, and editorial, Chris has always been a bit of a dark star. He loves shooting his Lecia. And he prefers black and white film. In the early 90s, when most pro photographers would only get their cameras out on cloudless, full sun days, Chris had no problem shooting black and white photos during the biggest storms of the season. While some of that had to do with the realities of weather in the Northwest, he also seemed to prefer it. As a senior photographer for both Transworld Snowboarding and Snowboarder magazines Chris traveled the world shooting snowboarding, yet, some of his best images are of snowboard heroes falling away into the shaded throat of some Mt. Baker powder slot with nothing but snow-laden trees, or a cliff line to frame the action. Though his photos ran in all the major magazines, some of his favorites were never published. That’s one of the reasons he is excited about his new book.

How Many Dreams in the Dark, marks Brunkhart’s return to snowboarding. After what Chris describes as a “falling out sort of” over Frequency Magazine in 2001, he disappeared from action sports media and spent several years working as a car mechanic and a finish carpenter—working with his hands and loving it. But with How Many Dreams he says everything has come full circle. The photos may be from the 90s, but for Chris this is a new beginning. Frequency Magazine is a sponsor, along with Volcom and Burton Snowboards, and everything seems to be right back on track.

How Many Dreams in the Dark, marks Brunkhart’s return to snowboarding. After what Chris describes as a “falling out sort of” over Frequency Magazine in 2001, he disappeared from action sports media and spent several years working as a car mechanic and a finish carpenter—working with his hands and loving it. But with How Many Dreams he says everything has come full circle. The photos may be from the 90s, but for Chris this is a new beginning. Frequency Magazine is a sponsor, along with Volcom and Burton Snowboards, and everything seems to be right back on track.

Follow the jump for the rest of the interviewIt is a warm day in mid August. Chris is seated in an roller-based business chair in the Tustin, California offices of Meridian Graphics. For someone who lives in a cabin on the outskirts Sandpoint, Idaho, Southern California must seem toxic. But Chris is publishing this collection himself, in the United States damn it, and he wants to make sure it gets done correctly. So he is here. Seated to his right is friend, and former Volcom corporate artist, Zach Egge. Zach is along for moral support (and van driving) as Chris spends every dollar he has and more to see his dreams made into reality.

Over Chris’ shoulder and behind a plate glass window, we watch workers prep a mammoth Mitsubishi Diamond 3000 eight-color press with ink and paper. Never mind that it took Chris nearly two years to edit, design, and finance the book not counting 15 years to shoot it, this Diamond 3000 will rip out one-thousand copies in about four minutes. The machine is ready. All Chris has to do is sign his name to a few more proofs and the switch will be flipped. It’s probably not the best time or place for an interview, but it’s where we are.

Over Chris’ shoulder and behind a plate glass window, we watch workers prep a mammoth Mitsubishi Diamond 3000 eight-color press with ink and paper. Never mind that it took Chris nearly two years to edit, design, and finance the book not counting 15 years to shoot it, this Diamond 3000 will rip out one-thousand copies in about four minutes. The machine is ready. All Chris has to do is sign his name to a few more proofs and the switch will be flipped. It’s probably not the best time or place for an interview, but it’s where we are.

Why now and why this?

My dad passed away a year and a half ago and that totally kicked me in the butt about following through with my dreams. If I don’t do it now when am I going to do it? So I might as well do it now and then I just delved deeply into the archives of 40,000 photos. Why this? Because I’ve been wanting to do a book for a decade. Everyone has been asking me about a book and I keep telling them, “I’m doing a book.” I just haven’t done it yet and it’s about time to do one. I came up with the idea of telling a story like in a raw format—unabridged media that is not controlled by the commercial ads and who’s who—just tell my story because some of the photos are ones magazines would never run. I think they tell a story of their own, but they’re not commercial. I love that shot of Craig right there [a photo of Craig digging into the back of his van on a trip to South America].There is a story behind every one of them. I wish i could have written a thousand words for each one.

How do you objectively go through and pick the photos that you think are the best?

It is not objective at all. It’s totally subjective. It’s totally my story. It’s what I want to say. I wanted to tell a story that I haven’t seen told before. I wanted to tell a Craig story or show photos of Jamil [Khan] or Jeffy [Anderson]. And document that whole golden age—or coming of age of snowboarding—that no one else is going to do.

If you have a photo that you thought was terrible, but you liked it do you put it in the book?

I don’t know. It’s hard because I went through 40,000 and whittled it down to a thousand and then had to pick 200 of those. It is hard because I have to make it interesting and it’s not just about bad photos, or just the photos I like. It’s got to be cohesive or tell a story. Time will tell if I’ve been good at it. With a lot of it the action spoke for itself, but there were these images that I’ve been calling environmental portraits that were people in a time and place. I was with them and I wanted to share those. All those shots about being on the road and the adventure and the stuff that got overlooked by photo editors because it wasn’t that high hitting action shot or whatever. That was a lot of the photos that are in here—photos that have never been seen because they’d been cast off, or I cast them off because I didn’t think they would sell.

You’re keeping the book compact and square. It’s not really a photo dimension?

I had seen the Taschen books that had that plasticized cover and I always dreamed of that because I wanted people to take it in their backpacks. I wanted it to get around like I got around. I didn’t want it to be this huge thing that sat on a coffee table and then got buried in magazines and then got moved to the bookshelf that no one ever saw. I figured if it was a little more compact someone else could take it with them and be inspired by it and it wouldn’t be so overwhelming.

When you’re looking at 40,000 images how do you know the photo and colors are properly reproduced?

It’s like I remember it. I remember that day. Not exactly. But I remember where I was. What that day was about. That’s what I try to bring back with me. The photos haven’t been altered, but they’ve been developed in a dark room. So I can achieve that to make it like I remember it. Not Photoshopped. Not enhanced. I don’t know what the word is. Ansel Adams had three books The Camera, The Negative, and The Print to get you through. It wasn’t just about the camera or the negative. It was about achieving what you saw that day.

How can you look through 40,000 images without getting entirely lost in them?

I didn’t really have a plan for the book. I just kind of knew what it was going to be about. We’d just go through negatives and just start circling things that stood out. I’d go, “I remember that photo.” I never even printed that photo and I would just go back through and scan and print all the stuff that I had circled. It was starting to be overwhelming and I was tossing things out. There was going to be a whole portrait section in the book but then they just sort of got integrated into it. Yeah, there is a whole other book coming sometime.

How many hours do you think spent putting the book together?

A mind boggling amount.

Did you find yourself going down wrong roads?

Like I said, I wanted to do a portrait section and I was going to be more creative with the design of it, but then the photos started speaking for themselves. And the strong ones kept sticking out higher and higher out of all the others. In the basement of my house I put up these cork walls and I started putting up 3×5 photos. There are like 1,000 of them. And I just started moving them around and making little groups like on the road, or traveling, or places of dreams. The photos started finding their own homes. Then there is a wall of crap. It wasn’t crap, they were still amazing, but I just couldn’t find out how to integrate them in so they started separating themselves. There were photo changes a week ago. I swapped a photos out from the sample I had to this sample.

There is no finality in digital. You can infinitely edit a story and infinitely switch out photos. But with a printed book it’s final. How do you draw the line and go, alright this is it?

Time, patience. The project had to have a end. And I hope this is the start of something more. For me being a photographer I want to share the story with people and share the ideas and dreams I have—and hopefully they’ll have their own. I hope this is the start of much more to come after my little hiatus. I think of this as the beginning—not finality. This is just a book. There are still photos out there. There are still prints, there are more books, there’s more whatever. I don’t know how I decided that this was it. There are sections on Craig that had to be there. I remember one day I had his section all done and I found another photo that was amazing. It was just cool to find another fucking sick photo of Craig. I was just like, “Again?” There’s a shot of Hetzel in the book up in front from Baker. And I was like, “How did I never . . . A. It’s Andy Hetzel. B. It’s Baker. C. I shot it.” I’d never had a shot of Hetzel run, ever. So some of the photos in there are definitely my little perk. Yeah, I got a photo of Andy Hetzel in there. There are half a dozen photos of Craig that no one has every seen before; portraits and action photos. It was that photo [page 85] which I thought was cool. You see his hike up. You see him boosting off on the shadows. I was in heaven.

All along you’ve had this antithetical view of snowboarding photography? Snowboarding is, especially when you started shooting, really bright, really white, really blue, and your photos are. . .

. . . darkness and full of mood shadows?

We used to give you shit all the time, “Did you take a dark, moody photo of . . . “

Everyone gives me shit for that.

They are beautiful, but was this your aesthetic or was it your response to the day?

It was my response to the day. And maybe my mood, and maybe the mood of the day, and maybe others. It’s like, some of those photos. . .

Are there any blue sky photos in here?

Yeah. You just passed a sequence of Craig [Kelly]. There is a blue sky day. .

. . . with no blue in it.

Oh, shut up. There.

Sometimes it almost seems like you were ignoring the obvious.

Yeah, maybe. I fell in love with black and white photography decades ago. Yeah, okay, I took the blue and the colors out, but—I don’t know what the right word is—I got to the essence of the photo, of the images, of the day, of the person, of the scene or whatever because I took the instant, or the obvious out. And I made myself look hard. I made other people look harder at it because it’s not the blue sky. I think sometimes if it’s that beautiful “whatever” photo people just say, “Oh yeah, another beautiful photo.” And they don’t look at it. And they don’t see all the other beauty. It’s not like it was intentional. And I grew up in the Northwest. That is an average day right there. That is always that day. What else was I supposed to do? Not shoot?

So what is the story behind the cover?

It’s Jamie’s [Lynn} crew the Ford Grenada Hard Core’s. They always had a little camp at the Baker Race and they would dig a snow cave. We were in it and it was dumping—typical Baker day just huge flakes. We were in there drinking beers, smoking when Ari peered in and I was there with my Leica. . . snapped. Always rolling X. I don’t know if he knows yet that he’s on the cover of my book.

You’ve done this book entirely by yourself. . .

Editor, publisher, marketer. I went out and raised the money. I’ve asked opinions and gotten help and critique from a handful of friends, Matt [Donahue] and Javas [Lehn] from Seattle and gotten input, but it was such a huge project that I couldn’t afford someone for two or more months to work on it. A lot of my other design friends had their own jobs and projects themselves. And, as I said earlier, it evolved by itself. It wasn’t something that I could say, “Hey, we’re starting March 1 and ending April 30th.” I’ve just been slowly designing it over the last year.

Did you have an end date in mind?

April (laughs). It’s now August. When I first started this last April (2009) I thought I would have it printed and shipped by Christmas and then go to the trade show with it. Yeah, right. It was a way bigger project than I ever imaged.

How did you get involved with the online funding site Kickstarter.com?

Two friends of mine, Stephanie and Zach, had both mentioned it to me earlier in the year. I looked at it and thought there were some other rules to get approved. I thought you had to get sponsored by someone who already had a project, so i just kind of blew it off. And then realizing how expensive this was going to be and how hard it was to come by corporate funding or sponsorship, I totally looked at it and it was awesome. I made $1,500 more than I asked for. People could sponsor it for $10, $25—and it was no risk for me or for them if it didn’t go through. The response from people I didn’t even know was really cool.

So you didn’t have corporate sponsors?

I did get help from Volcom and Burton. They totally helped out, but when I leave here I still have to sell books. They haven’t asked to okay anything. They just wrote me a check. It was really awesome. It took a little convincing and a little persistence, and I’ve gotten to be a better businessman through this deal—finally at 41 years old. But I kind of like how it’s homegrown. It wasn’t all done by company X who just paid for it. That was kind of the intent in a perfect world, “Yeah, give me a lot of money to do this. It will be cool.” But it became its own beast. Its own entity. And I did it all and I’m really proud of that fact. I went out and got sponsorship. I went out and designed it. I edited it. I spent 15 years photographing it. Whatever it is, it has all come full circle. Everything that has happened was meant to happen.

Epilogue

A pressman cuts in to interrupt our interview with a cup of coffee for Chris—probably his third or fourth of the morning—along with another proof that needs approval from the man writing the checks. Not surprisingly, after looking over the spread Chris has some input. “Is it possible to pump the blacks up a little and add a little more contrast in the shadows,” he says. “So those are like black, not black, but blacker? Does that make sense?”

Yeah, we think to ourselves laughing. It makes perfect sense.

The last stop of the How Many Dreams In The Dark book tour hits the New York City Volcom Store (446 Broadway) on Thursday, October 14, 2010 from 6 to 9 PM. The show features prints from the book along with art from Brunkhart collaborators Mike Parillo, Carl E. Smith, Matt Donahue, Alex Bacon, Dan Peterka, Zach Egge, and Jamie Lynn.

For more information follow Dreams in the Dark on Facebook, visit Chris’ website or click here to buy the book.

SUCH A GREAT INTERVIEW! Kudos Chris!

Serious yet fun journalism. great article. A good read. WOW boardistan. Compelling content. what the viewers want I would believe !!

Nice step up. Kudos to The Editors.

Comments on this entry are closed.